Introduction

In order to have a fruitful interaction between New Testament scholars, missiologists, and ministry practitioners, I am convinced that we need a shared framework of interpretation and action. We cannot assume that all of us agree on the meaning of mission, for example, when we start talking about mission in Acts or Acts in mission. It is helpful to discuss the meaning we give to basic terms, and the underlying assumptions of this shared enterprise we are embarking on. My paper has the dual purpose of developing a framework for missional interpretations of the Bible, and of illustrating the use of that framework by interpreting some reconciling encounters narrated in Luke-Acts in and for the South African context.

1. PART 1 INTERPRETIVE FRAMEWORK

1.1 Mission as (multi)dimensional

In the 1970s David Bosch started saying that mission is a wide, encompassing field of activity, with many dimensions. In Witness to the World (1980) he used the image of a prism, which refracts white light into the seven colours of the rainbow, to illustrate the integral unity of God’s one mission as well as the genuine differences between its dimensions. He insisted that we should not speak of the parts or components of mission (like evangelism and social action) that need to be kept in balance. That always leads to fruitless priority battles. Instead he proposed that we speak of the many dimensions of mission that need to be kept in creative tension with each other. We who were privileged to work with him in the Dept of Missiology at Unisa, found this view very helpful and so, as a department, we developed an undergraduate missiology curriculum in the early 1980s to express this vision. We designed modules with titles like Mission as evangelism and service, Mission as dialogue, Mission as liberation, Mission as African initiative, etc. And gradually we realized that the best way to express this “dimensional” approach to mission, was to use the expression “Mission as …”. That is also what David Bosch did in Transforming mission (Bosch 1991:368-510), when he proposed the 13 dimensions of his “postmodern ecumenical paradigm” of mission, which he called Mission as contextualization, Mission as inculturation, etc. A broad spectrum of activities, all of them validly part of inclusive or holistic Christian mission.

To my mind this was David Bosch’s most important contribution to missiology in South Africa. When he put forward this “dimensional” view of mission the 1970s, when we were still deep in apartheid, it helped us to counter that pernicious racist distinction between evangelism and mission that was common in the Dutch Reformed tradition in South Africa – and is still enshrined in some committee structures of DRC congregations and presbyteries – namely that mission is what white Christians do among black people, and evangelism is what they do among lapsed white Christians. It also helped us to get rid of the last vestiges of the romantic colonial idea that mission is what you do far away, across the waters, among “benighted heathens”, while evangelism is what you do among “civilized” post-Christian people.

Adopting Bosch’s dimensional approach to mission, I propose that we should also speak of Mission as reconciliation, since reconciliation is an integral dimension of the church’s mission on earth. It is interesting that David Bosch did not include “Mission as reconciliation” as one of the 13 dimensions of his post-modern, ecumenical paradigm of mission[1], particularly because that was perhaps the highest priority of his own public ministry in South Africa.[2] In terms of this “dimensional” understanding, Christian mission is not ONLY reconciliation; it encompasses a broad spectrum of activities, intimately linked to each other, and constantly interacting with each other, with no inherent priority assigned to any of these dimensions, since all are equally valid and indispensable to the project as a whole, even though in a specific context one or more of these dimensions may stand out as more important than the others, for that kairos moment in that particular place.

When we jointly look at mission in the Book of Acts, I propose that we consider using this multidimensional view of mission as a framework in which to work, as a shared vocabulary that we can use to talk to each other, even when we disagree about what we are saying.

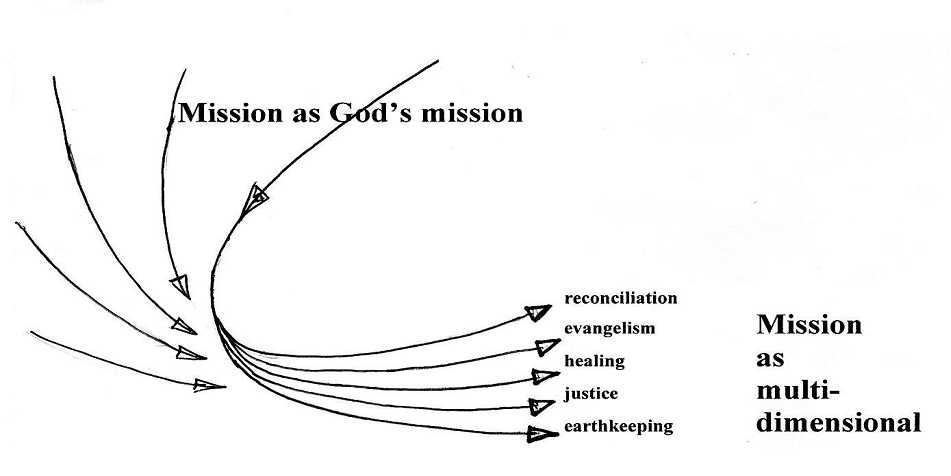

1.2 Mission as God’s mission

The second fundamental assumption that I propose for our joint efforts is to view this one multi-dimensional mission as God’s mission, as a divine initiative, therefore, rooted in the Trinity. The church’s mission (or missions) is then human participation in God’s work on earth. This clearly requires a good pneumatology, since the Holy Spirit establishes that delicate correlation between God’s work and human work, God’s gracious initiative and our faithful participation in it. Mission flows not merely from an external command (like the Great Commission), but from the outpouring of Spirit, which sets in motion an ongoing movement of people living in the power of the Spirit and by the guidance of the Spirit. The following diagram expresses this idea of mission as the multidimensional mission of God, thus combining this point and the previous one. The five dimensions of mission included in the diagram are not exhaustive, but merely a sample selection.

I propose to say that the church in mission – and the church as mission – lives epicletically. In other words, our lives are lived with empty hands and characterized by an epiklesis prayer: “Come, Creator Spirit! Come and make our human work to be part of God’s work on earth.” This shows the deep connection between Eucharist and mission, since the epiklesis is first and foremost a Eucharistic prayer. We learn to do mission at the Table, where we receive God’s grace with empty hands, having presented ourselves and our gifts to God, praying that God’s Spirit will transform our gifts (and us) into vehicles of Christ’s saving presence – thus making us the Body of Christ on earth. Christian mission is not mere human (or even Christian) activism, but the work of grace – in us and through us. It is, in the words of Phil 2:12-13, the way in which we “work out our own [collective][3] salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who is at work in us, enabling us both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (NRSV, adapted from 2nd person to 1st person). God is “the Great Energizer, the one who is effectively at work” in our mission (Hawthorne 1983:100).

1.3 Mission as praxis

Praxis is not the same as practice or action. It is the integration of theory and practice, of acting and thinking, praying and working. It is also:

a) Transformative: i.e., thinking-and-acting for change

b) Communal thinking-and-acting: i.e., not an individual matter.[4]

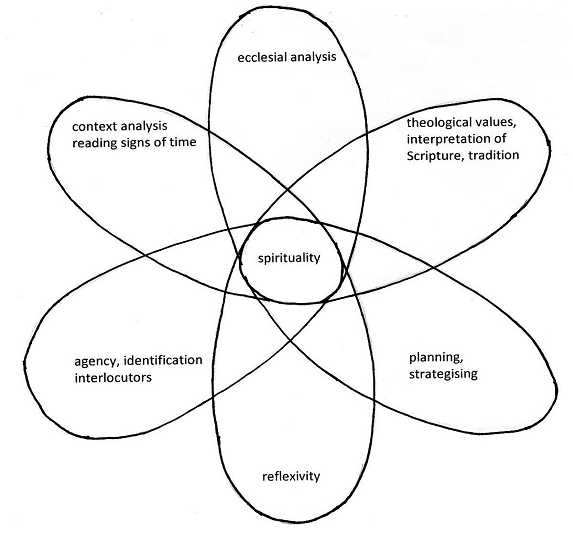

When engaging in any form of mission, i.e., any of the dimensions of God’s mission indicated above, there are certain features that need to be part of that transformative venture, if it is to be both faithful and relevant Christian mission. I prefer to use a praxis “cycle” or matrix with 7 dimensions, but it developed from a three-dimensional See-Judge-Act approach[5] into the classical four-dimensional “pastoral circle” of Holland & Henriot (1983) that consisted of Insertion-Analysis-Reflection-Planning. In South Africa, that was further developed into a seven-dimensional circle by Cochrane, De Gruchy & Petersen (1991), which I have followed to a large extent, as indicated in the diagram below.[6]

This praxis matrix is in its origin a mobilising framework, intended to help a committed group of Christians to contribute to transformation in their context. It is also possible, however, to use it as an analytical framework, to do research on the transformational attempts of others.

As I have indicated already, for me spirituality is at the heart of the praxis cycle or matrix.[7] The epiklesis at the centre from which it flows – and which holds it together – is what makes it Christian mission, distinguishing it from political propaganda, business entrepreneurship, or other forms of persuasive activism, even though the principles of all intentionally transformative projects are rather similar.

1.4 Mission as transformative encounters

Mission as praxis is about concrete transformation; it is specifically about transformative encounters: among people, and between the living God and people, leading to people being called, sent, healed, and empowered. It is about the Reign of God that has entered into this broken world as a transformative power in Jesus; that continues to be manifested transformatively in our midst by the work of the Holy Spirit; that takes hold of our lives and transforms us so that we may to encounter other people, thus creating the church as the community of the kingdom, working for and waiting for the coming Reign of God. God’s mission, the arriving of the Reign of God, is about transformative encounters. That is why missiology – which critically reflects on mission – is “encounterology”, the scholarly study of such transformative encounters.[8]

An example will help to explain this: In the theological exercise often called the “theology of religions”, scholars have set up a threefold typology of exclusivist, inclusivist, and pluralist approaches to other religions.[9] That is interesting and helpful, but if that is all you do, it may be acceptable as systematic theology but not as missiology. Missiology is interested in the actual encounters between people of different religions in specific contexts, about what happens when they encounter each other. For a missiologist it is not enough to know what a person’s theory of salvation (soteriology) is. To find out what her interfaith praxis is, you need to ask what her language his, her personal attitude to people of the other faith, her social position in relation to them, her prior experiences of that religious tradition, her analysis of the context, her spirituality, the concrete faith projects she is involved in, etc. Missiologists are interested in the praxis (i.e. the whole matrix) of interreligious encounter, not only in drawing up and refining soteriological “types” or models.

1.5 Mission as reconciliation

In this paper I limit myself to transformative encounters that can be described as reconciling. From the wide spectrum of dimensions that constitute God’s mission, I look only at this one, but without isolating or separating it from the other dimensions. I also limit myself to Luke-Acts, in line with the focus of the conference, and as an illustration of what I call a missional interpretation of the New Testament.

I can’t discuss it here, due to time constraints, but I need to mention that this theme, mission as reconciliation, is an important emphasis in contempoary missiological debate. A number of scholars have proposed that this should become the key focus for mission in this first half of the 21st century. I refer only to the work of Robert Schreiter (1992; 1997; 1998), Bill Burrows (1998), Kirsteen Kim (2005) and Ross Langmead (2008) as a representative sample. The title of Langmead’s article expresses this well: “Transformed relationships: Reconciliation as the central model for mission”. He explains: “What I am suggesting is that rather than Paul’s call in 2 Corinthians 5 for the church to be the servant of reconciliation merely being an isolated metaphor or a fleeting image, it has the potential to be a governing metaphor, a model that shapes our whole approach to mission and resonates on many levels” (Langmead 2008:7). Schreiter (1997:14f) paints the bigger picture when he says that whereas the mission model most common in the 19th century was “expansion”, and the most common model in the second half of the 20th century was “accompaniment”, the model of mission most needed at the beginning of the 21st century is “mission as reconciliation”. I am personally not in full agreement with this view; I am convinced that we should keep on emphasizing the multi-dimensionality of God’s mission, within which mission as reconciliation has a valid place alongside mission as evangelism, mission as liberation, mission as earthkeeping, and many others. But I agree that it is a key dimension of Christian mission today.

1.6 Missional interpretation of the New Testament

The final aspect of this methodological introduction is to focus on the dimension of Scriptural interpretation as integral dimension of the praxis matrix. I first need to say briefly what I mean by “missional”. For me this is an adjective derived from the noun “mission”, which I prefer instead of “missionary”, due to the negative connotations of the latter concept in the minds of many people today. I share many of the convictions of the Gospel and Our Culture Network (GOCN) and the “missional church” movement, but I do not use the concept to indicate that I stand solely and solidly under that banner. For me a “missional” interpretation of the Bible is one:

a) That emerges out of the practice of mission, that is, out of transformative Christian engagement in society;

b) That sees the New Testament as a collection of letters, pamphlets and booklets that were written in mission, as mission, for mission – as an integral part of the mission of the first century church;

c) That fosters better mission today: that is, it enables more authentic and more deeply transformative encounters with people and communities;

d) That expects the ongoing transformation of the interpreter-witness as much as the transformation of anyone else; an encounter is not transformative (in my understanding of this term) if it aims to transform only the “other” or a “target audience”;

e) That therefore uses all the dimensions of the praxis matrix as framework to integrate reading, thinking, analyzing, praying and planning.

There are two main possibilities of such missional interpretation, the one more reconstructive and the other more constructive:

a) A missional interpretation with a more reconstructive or historical emphasis uses the praxis matrix as framework to reconstruct as closely as possible how the early church did its mission; how these seven dimensions of the praxis matrix interacted to give early Christian mission its unique character and impact, but also its distinctly different trajectories and emphases, in the first century Mediterranean world.

b) A more constructive or mobilising interpretation reads the Bible within the praxis matrix to develop better mission praxis today in a specific context. This means focusing on the dimension of Scriptural interpretation (“theological values”) in the praxis matrix, but in constant interaction with the other six dimensions of the matrix, exploring the interaction or correlation between those dimensions in a specific contemporary context. This implies asking questions like: How can we discover in these stories the dynamic of God’s mission for today, for South Africa?; How can these stories mobilise God’s people today to live and work epicletically, within God’s mission, to continue the mission of Jesus, to embody those diverse dimensions of the one mission of God?

My intention with this paper is more constructive than reconstructive. However, due to the complexity of the praxis matrix and the contextualising process that it implies, this paper is merely a beginning of such a constructive interpretation. I hope that it will become a collaborative process involving a variety of colleagues, experts in different dimensions of the matrix, to produce constructive and relevant forms of reconciling praxis for South Africa today.

1.7 The integrity of the approach

The integrity or wholeness of this approach to interpeting the New Testament is hard to achieve, since it requires a delicate mutuality between these seven dimensions, carried by a spirituality at its heart. What also makes it difficult is the fact that it takes a group of believers, working together, to achieve this, so that a constructive interpersonal process needs to be set in motion. Due to this complexity we usually take “short cuts” across the matrix that leave out some of dimensions and overemphasise others.[10] We need a metaphor to help us understand how best to achieve such full synergy between the seven dimensions and between the different participants. One possiblity is the image of juggling: holding a number of issues “in the air” at the same time. This is helpful, but I prefer musical metaphors, since they seem to express most adequately the harmony and intricate mutuality between the seven dimensions.

Walsh and Keesmaat (2004) use the musical metaphor of “remixing” for their contemporary interpretation of Colossians to subvert the present-day empire. They describe their approach as follows:

[A]t its best, remixing is a matter of giving an older artistic expression new currency. In this sense, remixing is a matter of “revoicing,” allowing the original song to be sung again in a contemporary context that is culturally and aesthetically different. Such a remixing honors and respects the integrity and brilliance of the original piece while helping it to be heard anew in the ears and lives of people with different cultural sensibilities (Walsh and Keesmaat 2004:7).

This is what I try to do as well, admitting the danger of producing a bad imitation or even a “rip-off of the original author” (Walsh and Keesmaat 2004:7), even though that is not my intention (cf Kritzinger and Senokoane 2007:234). For me the seven-dimensional praxis matrix maps out the instruments, players, score, audience, and venue of the remixed “performance” of biblical passages that happens in missional interpretation. Hauerwas (2004), in his book Performing the faith, has given an illuminating reflection on the use of the musical metaphors of performance and improvisation to describe the nature of Christian reflection and self-understanding (Hauerwas 2004:78):

[U]nderstanding Christian existence as a kind of performance helpfully encapsulates the sense in which both the intelligibility and the assessment of faith are of one piece. That is to say the intelligibility (and hence the persuasiveness) of Christian faith springs not from independently formulated criteria, but from compelling renditions, faithful performances.

If we see the role of the Bible in the praxis matrix as the “score” of the musical/missional performance, then the other dimensions of the matrix represent the players, instruments, audience, venue, etc. which frame and situate the particular performance. And if “improvisation” is “the process of creating music in the course of performance” (Hauerwas 2004:79), then “elements of risk and unpredictable achievement are inescapable features of any good performance” (:80). If all of this sounds too dangerous, Hauerwas cautions:

[P]erformance that is truly improvisatory requires the kind of attentiveness, attunement, and alertness traditionally associated with contemplative prayer. All of which is to say that the virtuoso is played even as he or she plays. For music plays the performer as much as if not more than the performer plays the music; likewise language speaks the speaker as much as if not more than the speaker speaks the language (:81).

Having explained my method and framework of interpretation-action, let me now use the praxis matrix to create a remixed, improvised performance of some passages from Luke-Acts that may be intelligible – perhaps even persuasive and compelling – in the South African context.

PART 2 RECONCILING ENCOUNTERS IN LUKE-ACTS: A South African interpretation

Initially I announced my title as “profiles of reconciliation”, but I have decided to speak rather of reconciling encounters, not only because of my definition of mission as transformative encounters, but also because the dynamics of reconciliation, as the restoration of relationships between people, cannot be adequately grasped by looking only at the characters involved, in isolation from each other. It is necessary to look at the interaction between them to discover the concreteness and complexity of these transformative encounters. I selected the transformative encounters narrated in Luke 19:1-10 and Acts 9:1-31, which concern a number of interrelated transformative encounters. In these passages I discovered that reconciliation has to do with face-to-face encounters: facing the facts; facing the truth about my life; facing the music; facing the person I harmed (or who harmed me); and coming face to face with Jesus.

2.1 The selection of the passages

The dimension identified as “agency, identification, interlocutors” in the matrix above requires of one to explain who you are and where you come from, and what your interests or biases are, since these issues have a fundamental impact on how you interpret and embody a particular biblical passage. You have to show your own face, and not hide behind a mask of academic neutrality, political correctness, or doctrinal purity: “The performative logic of the Christian narrative is … inescapably self-involving” (Hauerwas 2004:84). One doesn’t necessarily have to start one’s performance with the “agency” dimension, but I do so here, since it gives my presentation more of a narrative character.

Why did I select these passages and encounters from Luke-Acts? And why do I call them stories of reconciliation? I could just as well have called them stories of salvation or of conversion. My approach or perspective on the passages is shaped by the need for reconciliation in South Africa, by the search to overcome the legacy of estrangement and separation that is still evident amongst us and between us. How did I select these passages? There are many other passages in the Bible (also in Luke-Acts, for the purpose of this conference) that I could have chosen. My reading of Scripture is shaped by my experiences, my reading of the South African situation, by my interlocutors (the people I meet regularly, who interrupt my self-pre-occupation and thereby shape the agenda of my life in a significant way).[11]

At the reunification discussions of the DRC family at the Achterberg conference centre (popularly known as Achterberg 1) in late 2006, I was asked to lead a short evening devotion at the end of the first day. I didn’t have time to prepare before the conference and I also wanted to sense what was happening in the meeting before deciding what passage to read, so as the evening discussion dragged on, with people stating their positions and staking their claims, I paged around in my Bible, wondering what would be a word from God for us in that context, a word that could ‘put us in our place’ within God’s mission. My thoughts gravitated towards Eph 2, Eph 4, Jn 17 – all the well-known passages – but for that situation they all felt too doctrinal, too flat, not imaginative or compelling enough. So I looked for a narrative, an encounter, and was eventually drawn to the encounter between Ananias and Saul in Acts 9. So in the devotion I read Acts 9:10-19 and said something like:

When we think of the miracles in the New Testament, we usually think of Jesus healing the sick, the blind and the lame, or even raising the dead; and that is true. But one of the greatest miracles in the New Testament happened when Ananias, the Christian disciple in Damascus, walked down Straight Street into the home of Judas, laid his hands on Saul and said to him … “Brother Saul”. It was not easy for Ananias to do that, as a persecuted follower of the Way, a potential victim of Saul’s fierce persecution of the church. You can imagine him saying to the Lord: “Lord, Saul is the enemy. You know how much harm he has done to your people in Jerusalem; and now he has come to Damascus to arrest us also. How do we know he is not trying to infiltrate our group by pretending to be a disciple, so that he can arrest all of us?” But the Lord convinced him to go and pray for Saul, his former enemy and persecutor. The miracle of reconciliation takes pace as Ananias places his hands on his former enemy and calls him “brother”. This is the kind of miracle we need today in South Africa: in the DRC family and in our communities at large.

When I was asked some time later to contribute a sermon to the series used in the annual Pentecost services (“Pinksterdienste”) of 2007, I developed those incipient ideas on Ananias into a sermon.[12] But as I prepared the sermon I added the figure of Zacchaeus, because Ananias alone does not give the whole picture of reconciliation (focusing only on the former victims who need to forgive). I heard in my mind the voices of black friends and colleagues, warning against cheap reconciliation, one-sided reconciliation, reconciliation without justice, amnesty without reparation – where the former victims (like Ananias) are expected to forgive and to accept those who harmed them, while the perpetrators never really admit their wrongs or change their lives. So I was moved by my interlocutors, by the realities of the South African context, and by my embarrassment at the numerous ways in which the Christian faith had been used in South Africa to keep people “in their place” (women, children, black people, gay people, etc.); I was moved not to speak of Ananias (the forgiving victim) in isolation, but to speak of him together with Zacchaeus (the repentant wrongdoer who embarks on restitution). But as I studied Acts 9, I suddenly noticed another reconciling figure. There at the end of the chapter was Barnabas, bringing the converted Saul and the congregation in Jerusalem together. So unexpectedly, once I started looking at Acts 9 with the question of reconciliation in my mind, there arose before my eyes also the face of Barnabas, the mediator, the negotiator, the peacemaker, agent of conflict resolution.

2.2 Three types of reconciling encounter

Having indicated why I selected these passages (Luke 19:1-10 and Acts 9:1-31), I look at them more closely. I will then move to the other dimensions of the praxis matrix, but return constantly to these passages, to show how this matrix, as an organic and interactive system, enables a missional interpretation of the Bible which amounts to an embodiment or an “improvised performance” of its message.

2.2.1 Jesus transforms wrongdoers to make restitution

2.2.1.1 Jesus face to face with Zacchaeus

Imagine the face of Zacchaeus when Jesus calls him down from the tree, when he walks home with Jesus, when they eat together at his table, when he gets up to confess his wrongdoing and make his commitment to restitution. Imagine the faces of the gossiping crowd, watching with horror or envy or disgust, pointing their long accusing fingers at Jesus and his disciples as they disappear with Zacchaeus into his mansion. Imagine the face of Jesus as he looks at Zacchaeus, meets his wife and children, spends the day with that family in their home. Imagine also the faces of the people whom Zacchaeus had cheated, when he knocked on their doors the next day, coming to return the money he had stolen from them! Imagine the face of Zacchaeus, as he explains to them what has happened to him, why he is there to make restitution.

You are never the same again when you have come face to face with Jesus. Zacchaeus was so surprised that someone noticed him, the envied-and-hated outsider, and took him seriously as a human being, that he opened his life to the message of the Reign of God. As a chief tax collector, collaborating with the Roman Empire, and as a corrupt official who enriched himself by abusing his power position, he was a persona non grata from the perspective of the vast majority of his Jewish compatriots. He was not the only Jew in Palestine who collaborated with the Empire, but he was one of the few who managed to enrich himself in the process. Most of his fellow Jews submitted themselves reluctantly to the military authority of Rome and to the Herods, Rome’s proxy rulers in the region. But in the eyes of the people of Jericho, Zaccheaus was a traitor and a crook – an outsider, definitely excluded from the faith community, and labelled a “sinner” [hamartolos] in Lk 19:7.

When Jesus, the Good Shepherd, seeking and saving the lost (Lk 19:10), took the initiative to invite himself to Zaccheaus’s home and entered it, Zacchaeus no longer needed to see himself as an outcast. Although he was a perpetrator of injustice, he was also a victim of social ostracism and exclusion. Jesus starts by addressing Zacchaeus’s religious-cultural exclusion, by seeing him first as a victim, not as a sinner but as one sinned against, and overcoming that exclusion and victimhood through unconditional trust in him and acceptance of him as a human being: “I must stay at your house today” (Lk 19:5). By breaking through the “purity system” with its taboos and restrictions, Jesus initiates the process of reconciliation in Zacchaeus’s life, by starting with his victimhood. Schreiter (1998:14f) has pointed out that reconciliation is the work of God, and that God “begins with the victim”, by restoring their humanity. Putting this in other words, one could say that the first word of the gospel for oppressed and/or excluded people is not “Turn around!”, but “Get up!” (see Kritzinger 1990:42).

Once you are standing, however, you hear that other word of the gospel: “Turn around!” It is clear that Zacchaeus heard both these words from Jesus. When his broken and shattered humanity began to be restored, the ugly reality of his life dawned on him and he realized just how much injustice he had done to his neighbours. Why does the text say that he stood (Lk 19:8) when he spoke to Jesus? I imagine that it was to emphasize the solemnity of his declaration. I imagine that is what during the meal that he became aware of his life and decided to turn around. So he got up from the meal, walked over to Jesus, stood in front of him and spoke to him face to face (eipen pros ton kurion). He got up not only to get everyone’s attention, but also to take a solemn oath of allegiance to Jesus as Lord, committing himself to the radical lifestyle change that it demanded from him. In response to this, Jesus declared that Zacchaeus was also a child of Abraham (Lk 19:9), that he was no longer an outsider, but an insider to God’s covenant promises, since salvation had come to his home.

Zacchaeus was not just sorry about what he did; he was thinking differently about his life, and decided to do something about it. When he took himself out of the centre of his life and started building it around the Reign of God appearing in Jesus, he realized that he would have to make restitution, to make right what he had done wrong, and try to restore all the relationships that he had broken with his injustice. Having come face to face with the truth in Jesus, he now had to go and face the people he had harmed.

It would take him a long time to reach everyone he had harmed, but the important thing to understand is that it was not only about giving back money. By giving back the money he re-established the justice that he had earlier destroyed, as he tried to restore his relationship with the people he had hurt. This is what reconciliation is: not alleviating an individual guilty conscience, but restoring broken or damaged relationships. The restitution that Zacchaeus embarks on is not about buying people’s favour. We can never force anyone to forgive us, least of all by offering them money. Forgiveness remains a decision, often a painful one, which only the injured party can make. But with Zacchaeus we can follow the way of Exodus 21, which shows us that justice means to make right what you did wrong; to pay compensation if you harmed someone. When God’s salvation enters Zacchaeus’s home, he converts himself to his neighbours, and he starts walking down Reconciliation Road, in which he no longer exploits people, and pays reparation to those he harmed.

2.2.1.2 Jesus face to face with Saul (Acts 9:1-9)

The face of Saul is similar to that of Zacchaeus. Like Zacchaeus, Saul is a perpetrator of injustice. He was “breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord” (Ac 9:1) and he had committed various acts of violence against them (Ac 8:3; cf. Gaventa 1986:55f), merely for being followers of the Way, which he regarded as an evil that needed to be stamped out from Israel in the “zealous” tradition of Phinehas and Jehu (Hengel 1979:83). Like in the case of Zacchaeus, Jesus is the one who takes the initiative. Neither Zacchaeus nor Saul invited Jesus into their lives. Quite the contrary! Like Zacchaeus, Saul committed himself to a radically new way of life, after coming face to face with the ascended Lord. One could say that the Saul/Paul made restitution for his wrongful persecution of the church by committing the rest of his life in service of the gospel.

In the case of Saul, Jesus could not invite himself to lunch. Instead, he confronted him with a haunting question, as poignant as the question of the Creator to Adam: “Where are you?” (Gen 3:9) or to Cain: “Where is your brother Abel?” (Gen 4:9). A few things are significant about this question:

a) It was spoken in Aramaic. We can see this from the form of the name in Ac 9:4 (Saoul, not Saule). It is also stated pertinently in the parallel narrative in Ac 26:14, “I heard a voice saying to me in the Hebrew language”. Why did the ascended Jesus speak to Saul in his first language? Because this was the language of his heart, the language in which he prayed and dreamed. Although he was a Roman citizen and fluent in Greek, the ascended Lord speaks to him at the deepest level of his existence, because the kind of change required of him was at the level of his worldview and ultimate assumptions. The reconciliation into which the ascended Lord calls Saul includes the restoration of Saul’s broken relationship with himself; it is a call to authenticity and a genuine humanity; and that kind of business is not done in your second language![13]

b) The exact wording of the question is also interesting. The repetition of someone’s name (for emphasis) was found in key Old Testament passages, all of them in passages that Lohfink (1976:61ff) calls “apparition dialogues” (Gen 22:11 -Abraham; Gen 46:2 – Jacob; Ex 3:4 – Moses; 1 Sam 3:4 – Samuel; cf Gaventa 1986:58). Such double appellations are also found a few times in Luke’s Gospel (Lk 8:24 – Master; Lk 10:41 – Martha; Lk 13:34 – Jerusalem; Lk 22:31 – Simon; cf Haenchen 1971:322). I cannot escape the hunch, however, that this expression “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” also resonates with that other haunting question of Jesus; “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mt 27:46; Mk 15:34, from Ps 22:1). Both of these sayings were spoken in Aramaic, and are very similar in structure. Haenchen (1971:322) suggests that the Aramaic could have read “Shaul, Shaul, lema tirdefeni?”, whereas Dalman (1929:18) thinks of “Shaul, Shaul, ma att radephinni?” It is striking that Luke did not include the words of Psalm 22:1 on the lips of Jesus in his narrative of the crucifixion, even though both Mark and Matthew did that.[14] In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus on the cross prays for his enemies (Lk 23:34), pronounces entry into paradise for a repentant criminal (Lk 23:43), and commits his life into the hands of his Father (Lk 23:46). In Luke-Acts, it is not the crucified Jesus who utters a lament to God outside the gate of Jerusalem, but the ascended Jesus who utters a lament outside the gate of Damascus – to Saul, persecutor of the church: “Shaul, Shaul, lema radaftani” or “Shaul, Shaul, lema tirdefeni“. This parallel helps us to see that Jesus’s question to Saul is not a rejection but an accusation in the form of a lament, which expresses trust – not rejection, despair or cynicism – just as was the case with Psalm 22 on the cross. The suffering believer of Psalm 22 expressed his lament to God (Ps 22:1-2) on the basis of God’s faithfulness to his ancestors (Ps 22:4-5). He expected more from God, on the basis of God’s promises.[15] The ascended Jesus implicitly says to Saul: “I expect more from you. This is not who you really are”. And he said it to him in Aramaic, the language of his heart.

c) The last aspect of this question that we need to note is that the ascended Jesus identifies himself fully with his suffering followers: “Why do you persecute me?” Schreiter (1998:15) has written, with reference to reconciliation in general:

God begins with the victim, restoring to the victim the humanity which the wrongdoer has tried to wrest away or to destroy. This restoration of humanity might be considered the very heart of reconciliation…. It is in the ultimate victim, God’s son Jesus Christ, that God begins the process that leads to the reconciliation of the whole world in Christ.

Nowhere is this more true than in the reconciliation between Jesus and Saul. The crucified Jesus was a victim of persecution by the forces of Empire, in league with opportunistic religious forces in Israel, who tried to destroy his work, to wrest his humanity away from him. They seem to succeed, and he dies on the cross, but God raises him from the dead and 40 days later he ascends into heaven. And now he continues his mission on earth, the Victim whose human dignity has been restored, and who suffers with his persecuted disciples. And now he comes to Saul, with the same attitude as his prayer on the cross (“Father, forgive them; they don’t know what they are doing”, Lk 23:34), and the words of Stephen (“Lord, do not hold this sin against them”, Ac 7:60), which both express trust that they should know better. The crucified-and-ascended Jesus narrated to us in Luke expects more from his enemies; he appeals to his Father on their behalf and he appeals to them directly: “Why do you have to persecute me? Why must this to go on? This is not who you really are! You can and should do better than this!” At the heart of Gods’ work of reconciliation through Jesus Christ there is the fundamental belief that people can change, that enemies can become friends, the astounding trust that enemies can come to know what they are doing, can recognize who Jesus really is, can stop persecuting him in his followers, and can become reconciled to him and to them.

It may be helpful to reflect for a moment on the means that the ascended Christ used to confront Saul with his own evil. Was it an act of violence to be struck with temporary blindness (Acts 9:8)? Perhaps in some way it was, much like the overturning of the tables in the temple (Mk 11:15 and Mt 21:12), which is not included in Luke’s Gospel. The temple incident and the blinding light at the gate of Damascus are presented not as acts of brute power or violent revolution but as prophetic acts to expose injustice, as appeals to the consciences of the wrongdoer(s) to stop their abuse of power. This idea is expressed well by Neven (2009:1), when he speaks of “a nearness of salvation which does not, as it were, supernaturally demolish time and history, but rather breaks open time and history from within – messianically”.[16]

Saul responded to this question, and to the blinding light, by putting his trust in Christ, by turning away from the way of violence and committing himself to live a life of witness and obedience. As I said above, it would not be inappropriate to see Saul’s life of tireless witness to Christ as a lifelong commitment of restitution for the evil and injustice he had done to Christ and his followers. It also helps us to see that a lifelong commitment to restitution is not driven by a sick guilt feeling, but by joyful devotion to the gracious Lord, who forgives our wrongdoing and calls us out of the darkness of injustice and violence into the light of love and peace.

2.2.1.3 Transforming wrongdoers to make restitution today

Within the space of one paper it is impossible to bring together all the dimensions of the praxis matrix with any depth. If this proposal makes sense, it could become an ongoing research-and-service project engaged in by a group of colleagues, which would integrate all the dimensions of the matrix. What I can do here is only to indicate briefly the kind of issues that arise when we relate the interpretation of the two passages above to the other dimensions of the matrix. The basic question here is: What could (or should) the church’s ministry be in encountering people who committed evil and injustice, when we look for impulses from these two reconciling encounters? For each dimension of the matrix I will indicate the kind of questions that may arise.

a) Spirituality: How can we avoid fostering a paralysing guilt complex, which prevents a humble-and-joyful lifelong commitment to restitution? Some Afrikaners say: “How many times must we still confess that apartheid was wrong? Must we keep on saying we are sorry?” This is a misunderstanding of the dynamics of reconciliation. The message of God’s grace in Christ for wrongdoers is about a cancellation of guilt that leads to a life of discipleship, part of which is a commitment to restitution, which is the desire to restore the relationship with the people you have harmed. It is not about feeling guilty for the rest of your life, or about continuous self-flagellation. There will be times and places where it will be appropriate and necessary, in order to open the way for reconciliation with a particular person or group, to confess to the person(s) you have harmed – privately or publicly – that you are deeply sorry about the wrong they suffered and about your share in it. But a mature, grace-centred spirituality will guide us to avoid the two extremes of a) ignoring/denying our complicity in past evil, and b) bending over backwards with an unhealthy guilt complex, and over-compensating for our wrong. Both these approaches block the possibility of restoring the broken relationship with our former victims/survivors, since they amount to a denial of the priority of grace, and a disrespect for ourselves as well as for the other(s).

b) Context analysis: When one tries to understand the South African context with a view to reconciliation, there are important structural and systemic dimensions to the question. Reconciliation between individuals is hindered or prevented by the attitudes, policies, laws and structures from the past that have alienated people and communities from each other. The memory of past evil and injustice, lingering for years and even decades or centuries in the minds and stories of the victims/survivors, effectively sours the relationship between the descendants of the original role payers. In addition to the memory of past evil, there is also the enduring reality of suffering and injustice, which is the result of policies and practices of the past, and which continues to bedevil human relationships in the present.

We therefore need to employ notions of personal and systemic sin, as well as interpersonal and social reconciliation (see Schreiter 1998:111-116), if we wish to come to terms with this situation. However, it is not helpful simply to transfer the dynamics of interpersonal reconciliation onto social reconciliation. A key question therefore is: What are the unique dynamics of interpersonal and social reconciliation respectively, and how are these two processes related to each other? An ongoing project will have to tackle this question as a matter of priority.

c) Following directly from the previous point, is the question whether South African churches and theologians have given sufficient attention to the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). What is there in the TRC report that we could/should develop further as churches/theologians? The TRC was never meant to complete the reconciliation process in South Africa. The recent book by Krog, Mpolweni and Ratele (2009) is one example of how a testimony before the TRC can be engaged with, not only to understand “what was said then”, but also to foster reconciling processes amongst us today. It would be helpful to follow the example of Krog and her colleagues by establishing small intercultural groups of church ministers and theologians to grapple with an interpretation of specific TRC testimonies and the role that Christian faith can play to bring about reconciliation in relation to them.

d) Context analysis: Flowing from the previous point, a distinction needs to be made between perpetrators and beneficiaries of injustice. It is best to illustrate this need with a story: Recently a group of black theological students of the URCSA studying at UP visited the Hector Peterson memorial in Soweto together with some fellow theological students from the DRC and some visiting students from the USA. Some time after the visit, the students said (in a discussion) that the Hector Peterson memorial “is not a place to visit with white people” since “it only makes you angry”. What had made them angry was that the white students said at the memorial: “We were not even born when this happened”, without any acknowledgement of their connectedness with their parents and grandparents who had been born at the time and without owning up to the fact that they had benefited from their “whiteness”, even though they were never in the position to support or perpetrate apartheid. The unwillingness or inability to acknowledge white privilege flowing from the apartheid system is a serious obstacle to reconciliation in South Africa, and it will have to be addressed in a reconciling mission praxis.

e) Context analysis: Another set of questions arising from the search for reconciliation in South Africa deals with land ownership. The racist maldistribution of land enshrined in the Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 has been endorsed by the present Constitution, even though there is provision for a systematic and orderly redistribution of land, as well as restitution for communities that were forcibly removed from their land under apartheid. Since social reconciliation involves not only the restoration of interpersonal relationships, but also reconciliation with the land and the soil, to be “planted”, as this is expressed in that vivid metaphor of return from exile in the Old Testament. There are thousands (millions?) of uprooted and rootless people in South Africa who need to find security and solidness through being planted firmly in the soil of Africa. Numerous questions flow from these statements, if one wishes to let them contribute to deepening reconciling praxis in South Africa today and to relate them to the other dimensions of the praxis matrix. Some of these are: To whom does (and did) South Africa belong? How far do you go back in history to decide this? Is private land ownership ethically and environmentally justifiable?

f) Strategy: When it comes to the strategic dimension of reconciling praxis, we should ask questions like: How can churches play a role in facilitating the government’s land reform programmes? What other projects of interpersonal encounter can churches and NGOs engage in, to facilitate the acknowledgement of white privilege under apartheid and to move beyond closed ideological positions (involving mere blame and defence strategies) into restitutional actions that can contribute to broader reconciliation?

g) Systematic reflection: When do you stop seeing your social justice commitment as “restitution”? When have you “paid off” your “debt”? Or is that the wrong way to look at this? Is restitution about carefully calculated (perhaps even audited) financial statements in which we struggle to pay off the outstanding balance, like with a mortgage on a property? And may the victims/survivors “charge interest” on the outstanding amount so that it becomes more and more difficult to pay off, so that some people lose hope and decide to give up? We do well to link restitution to restoration, to avoid such a quantitative misunderstanding (and possible abuse) of reconciliation as restitution. Whatever else it is, restitution is not about being plagued by a guilty conscience and therefore being unnaturally “nice” to “make up” for what happened. It is about a deeply humble sense of having been forgiven by grace for injustice done in the past, leading to a radical commitment – “half of my possessions I will give to the poor” (Lk 19:8) as well as a lifelong commitment to a new way of life –

Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. For I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God. But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace toward me has not been in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them– though it was not I, but the grace of God that is with me (1 Cor 15:8-9).

h) Ecclesial analysis: In order to do justice to what the church has already done about this, we need to collect stories of Christians (as individuals and congregations) who are living lives of making restitution.

i) Strategy/planning: What role should language(s) play in reconciliation? If reconciliation between Jesus and Saul happened in Aramaic, what does that say about our languages of worship, and of church unity negotiations or ecumenical discussions? How can we create interlingual and intercultural “spaces” where deep and reconciling human encounter can take place? How can interpretation between the languages of be facilitated that can How can we avoid a repentant powerful person or group from manipulating or controlling a reconciling process through the use of a dominant language, without understanding (or even hearing) what the hurt or oppressed person is saying?

j) Reconciliation is obstructed more than anything else by the mind we have already made up about the other. We have painted him, her, them into a corner – and thereby painted ourselves into the other corner. We must overcome such sterile polarization by following in the footsteps of Jesus. But this implies taking sides, approaching the powerful from a position of solidarity with the powerless. Is God in a special sense the God of the poor, suffering, oppressed, as the Confession of Belhar would have it? Yes. This is abundantly clear, not only from the OT prophets like Amos, Isaiah and Jeremiah, but also from NT passages like Mt 25:31-46, and above all from this loving, humanizing question of the risen, ascended and glorified Christ: “Why do you persecute me? When you touch one of these little ones, you touch me!” However, this side-taking of the ascended-but-not-absent Christ is not a rejection of the powerful who are oppressing, exploiting or persecuting the little ones. It is not an closed, ideological side-taking in which the strong, the rich and the powerful are rejected or made into enemies (all over again). On the contrary, it is a side-taking aimed at reconciliation, at the justice of God without which no peace is possible, at the restoration of broken relationships. It is therefore the disappointed, agonising and deeply loving question of Christ, directed at the powerful in the form of a lament question: Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? Jerusalem, Jerusalem, why do refuse to let me gather you together under my wings of justice? Zacchaeus, Zacchaeus, why do you exploit and defraud me? Why do you underpay me? Why do you rape me? Why do you call me a ….? It is a side-taking aimed at the conversion of the oppressor, his or her liberation from corruption by power, money, religion and privilege, and into a lifelong commitment to grace-based restitution.

2.2.2 Jesus transforms victims/survivors to forgive their former enemies

2.2.2.1 Jesus face to face with Ananias (Acts 9:10-19)

Ananias was unwilling to go and pray for Saul of Tarsus. As I have pointed out before, he had good reasons to refuse. It took much persuasion for the Lord to get Ananias to walk to the house of Judas to find Saul. Without the “double vision”[17] that Luke reports to us, Ananias would not have risked approaching Saul. Perhaps that is the longest journey in the world – the road a victim must travel to reach the home of his persecutor, the road of the humiliated and disadvantaged person to face and to forgive someone who exploited or harmed her. The most difficult part of that long journey is the last 50 centimetres: to get close enough to your former enemy to touch him or her; and by that touch – in the name of Jesus – to break the power of enmity, fear, disappointment, revulsion, even hatred.

Where do victims find the courage to face – and to forgive – their persecutors, their former enemies and oppressors? This requires a living spirituality, a deep and honest relationship with God. It cannot happen if their broken or shattered humanity has not been (at least partially) restored through the message of God’s love, acceptance by fellow believers and the encouragement of the Holy Spirit. Schreiter (1998:14) emphasises that reconciliation is the work of God. In Acts 9, it was the ascended Christ who took the initiative to stop Saul in his tracks, and to persuade Ananias to go and pray for him. Ananias would probably not have gone to pray for Saul if the Lord could not convinced him that Saul had already changed; that he was in fact praying at that very moment (Ac 11). It makes it so much easier to reconcile with someone who hurt or oppressed us if we know beforehand that the person has already embarked on the road of repentance and renewal. But even when s/he has not yet changed – or when we don’t know whether the change is genuine – the love of Christ urges us to start making peace with them in our minds and hearts, to develop an attitude and willingness to forgive. If I am unable to do that, I risk allowing the injustice and pain done to me to poison my life; then my red hot anger can turn into ice cold hatred or dark depression. Then we allow our suffering to make us bitter, scarred victims who are unable to transcend victimhood. The victim/survivor is then “held hostage by unrepentant wrongdoers” (Schreiter 2005:4).

But this does not mean that forgiveness is ever easy. Ananias talked back at the Lord, and objected when the Lord told him to go and pray for Saul. With a robust spirituality reminiscent of the Psalms, Ananias wrestles with the Lord about this. Reconciliation is not a superficial or cheap exercise that “papers over the cracks”. When reconciliation is genuine and honest, it is accompanied by pain, often by confrontation, since reconciliation is about the healing of wounds and the restoration of broken relationships. It is also about the struggle against my own refusal to reconcile, to find a way out of the dark cave of my hatred in which I hide from God and my neighbours. Sometimes we nurse our wounds and feel sorry for ourselves; at other times we hide and suppress our wounds or deny them; then again we exhibit them to try and get some sympathy from others. In all these strategies we block the possibility of reconciliation with those who hurt us. And thereby we block the mission of God in this world.

The face of Ananias is that of the hesitant, reluctant, apprehensive victims (or potential or former victims) who face up to their former enemies or oppressors and takes the risk of beginning a new relationship with them – even when there is no guarantee that the others have really changed – and who walk down Straight Street, urged and moved by the love of Christ[18] that they have experienced in their own lives.

2.2.2.2 Empowering survivors to forgive

When the other dimensions of the matrix are brought into play, the following kinds of issues arise:

a) Strategy: An essential strategy is to allow victims/survivors of violence or trauma to tell their stories. Schreiter (2005:5) speaks of “truth-telling” that involves “breaking the codes of silence that hide wrongdoing against the poor and vulnerable of society”. However, the question is how churches can help victims, survivors, wrongdoers and beneficiaries to meet in truth-telling encounters to form healing communities, where forgiveness can begin to happen?

b) Spirituality: How can worship, rituals and spiritual exercises help people to be set free from the power of the past, and learn to forgive? Forgiving is not to forget but to “remember in a different way – a way that removes the toxin from the experience for the victim and creates the space for repentance and apology by the wrongdoer” (Schreiter 2005:4). For the church to play this kind of role, it should create “communities of safety, memory and hope” (Schreiter 1998:116)? How do we ensure that the priority of God’s gracious initiative is maintained in our reconciliation processes?

c) Context analysis: It is important to notice and examine the different strategies of exclusion prevalent in our society. Miroslav Volf (1996) has pointed out how exclusion and violence start with language; with the way we speak about ourselves and others. A context analysis that is done within a praxis matrix – driven by the desire to understand what is going on in society and by a deep concern for reconciliation – will use inclusive rather than exclusive language. By this I do not only mean avoiding gender exclusive terms like “mankind” but more fundamentally that we should think and speak of “us” and “our” when we analyse our communities. We should not say: “The Afrikaners have a problem of racism; The Coloureds have a problem of gangsterism; The Blacks have a problem of poverty”. We should rather say: We have a problem of drug abuse in some of our townships or suburbs. These are all our children. The three young men who stole my car at gunpoint a few years ago are not their children who have gone off the rails; they are also my children, young men in their early twenties who might as well have been sitting in the class of our theological seminary. The terms that we use to describe our communities are the first acts of inclusion and reconciliation, or – if we use stereotyped, exclusionary language – they are the first steps in the wrong direction. Volf (1996:75) has pointed out that exclusion can take four different forms: a) elimination (‘the only good … is a dead …’); b) assimilation (‘they’ must become ‘like us’); c) domination (‘they’ must know ‘their place’); d) apathy or indifference (‘they leave me cold’). Where such attitudes and patterns of action prevail, we have a fundamentally unreconciled society.

d) Spirituality: Flowing from the previous point, a praxis matrix devoted to reconciliation will breathe a spirituality of inclusivity and convergence. As Volf has so movingly described it, the “drama of embrace” has four stages: a) you open your arms to the other; b) you wait for her/him to do the same; c) you both close your arms around the other in a mutual embrace; d) you open your arms again to let him/her go. This spirituality of embrace will guide us when we face painful questions like: Can I expect a victim/survivor to forgive me as a wrongdoer if I have not (yet) apologised or confessed my wrong? Can I expect (or pressurise) a victim/survivor to forgive me when I have apologised? In this way we can develop a contextual ethic of forgiveness, which is an essential dimension of reconciling praxis.

2.2.3 A Christian leader mediates between colleagues (Acts 9:26-28)

The third and final reconciling encounter in Luke-Acts that I wish to mention here is the mediating intervention of Barnabas as told in Acts 9:26-28. If it was hard for Ananias and the other followers of Jesus in Damascus to accept and forgive Saul of Tarsus, can you imagine how difficult it must have been for the Christian community in Jerusalem to welcome him into their fellowship. After all, it was there that he did most of his damage to the church; where he had many followers of the Way arrested and dragged before the Sanhedrin to be put in jail for their faith (Ac 8:8). It was there that he approvingly witnessed the stoning of Stephen and the scattering of the early Christian community (Ac 8:1). How could the congregation that was left in Jerusalem forgive and accept him?

There are many such broken relationships in the world. And they often do not get healed unless someone comes from the outside as a mediator. Barnabas was such a mediator, a peacemaker who took the initiative to bring the two parties together, without anyone asking him or paying him for it. Barnabas had recognized the potential of Saul as a Christian witness; he also realized that Saul would get nowhere if he was not accepted by the leaders of the Christian movement in Jerusalem. As so often in history, the unity of the church was at stake in a very pertinent way. It sounds so simple in Acts 9:27f: “Barnabas took him, brought him to the apostles, and described for them …. So he went in and out among them in Jerusalem, speaking boldly in the name of the Lord”. Barnabas told them that Saul had seen the Lord on the way to Damascus, that the Lord had spoken to him, and that he had openly preached in the name of Jesus in Damascus. These three pieces of testimony, on the authority of Barnabas, opened the door for Saul to be welcomed and taken up into the heart of the Jesus movement of that time. It was an important event in the history of the church, as portrayed by Luke. According to Acts, Saul’s ministry would not have been authentic without this reconciliation between Saul and the church of Jerusalem.

Barnabas saw the problem, took Saul’s hand, walked with him to the church leaders in Jerusalem; and helped them to accept one another. In this way the showed himself to be indeed a “son of encouragement”, as Luke introduces him to Theophilus and his other readers in Acts 4:36. It is a good question whether “encouragement” is the best way to translate the Greek word paraklesis. I wonder if huios parakleseos should not rather be translated as counsellor or peacemaker. What was significant about Barnabas was that he had enough credibility on both sides of the conflict, which enabled him to act as a bridge-builder between them. He noticed an unreconciled relationship and took the initiative to do something about it. The face of Barnabas is that of the concerned citizen, playing an active mediating and peacemaking role in and between churches, and in the community at large.

This reconciling encounter is different from the previous two, where the encounter was in the first place between Jesus and a wrongdoer (Zacchaeus, Saul) or between Jesus and a victim/survivor (Ananias), leading to a second phase of reconciling encounter between the repentant wrongdoer and his former victims. Here, with Barnabas, we find a reconciled Christian leader, who mediates between colleagues, without the name of Jesus being mentioned explicitly. And yet his action embodies the spirit of Jesus, perhaps particularly that other lament of the Lukan Jesus, his faced turned towards the holy city: “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing!” (Lk 13:34). Barnabas wants to gather God’s people together in unity, to build bridges of trust and acceptance between them, thus expressing this “mothering” ministry of God revealed in Jesus.

2.2.3.1 Developing mediating leadership in churches and communities

The kinds of issues that could come up here, when one “thickens” the interpretation given above into full-blown praxis matrix:

a) Strategy: How can ministerial formation (theological education) contribute to producing leaders with good conflict resolution skills, with the ability to see relationships that have become problematic, and the love and patience to guide others along the way of reconciliation? Once more, what is the role of different languages in such a ministry of peacemaking?

b) Context analysis: Collecting stories of Christians who are playing such proactive reconciling roles in communities, and using them to try and draw

c) Spirituality: What kind of spiritual exercises contribute to a peacemaking leadership style?

d) Agency: Who is qualified to play such a role? A “Barnabatic” figure is someone who has enough credibility on both sides of the conflict in order to serve as mediator between them. A high priority for the reconciling mission of the church in society is to prepare and develop as many Barnabatic figures as possible who can act as links and bridges across all the “fault lines” of our society.

e) Systematic reflection: When we think of public, social reconciliation it is important to avoid “perfectionism” in the sense that we expect too much too soon. As Schreiter (1998) has pointed out, social reconciliation is a long process, and every forward step is therefore helpful. In this regard the contribution by Wim Overdiep (1976) is helpful, particularly his “emotional distance scale”. He distinguishes five types of emotional distance between people: enemies, opponents, strangers, colleagues or friends. The first and the last (enemies and friends) are closest to a person emotionally, whereas strangers are emotionally the furthest away, since they are the people who “leave you cold.” The remaining two positions of opponent and colleague fall between these two extremes. The following diagram expresses this framework:

Friend

(like) Colleague

(appreciation, cooperation)

I Stranger (indifference, neglect)

Opponent

Enemy (respect, confrontation))

(dislike)

According to Overdiep, reconciliation does not require all enemies to become friends, since that is an unrealistic expectation. For reconciliation to (begin to) take place, it is sufficient that they become opponents, that is, people who play the same game on the same field and according to the same rules, actively opposing each other but with respect, thus leaving behind the bitterness of the battle which was evident when they were enemies. A reconciled society will have as few enemies and strangers as possible, and put in place processes to help them move from those roles into the roles of opponents, colleagues or friends.

2.3 The way forward

This paper presents little more than a framework and an agenda for reconciling praxis in South Africa. The role of each dimension of the praxis matrix needs to be properly developed, but this can only happen when a group of committed colleagues – coming from different language, gender, class and academic discipline backgrounds – begin to work together on developing and carrying out such a reconciling praxis. In that way we can produce the kind of contextualized, improvised performance of the gospel of reconciliation that South Africa needs today. In terms of my musical metaphor, I have played the basic melody of this piece in a solo performance here; it is now time for the “jamming session” to start.

REFERENCES

Bosch, David J. 1980. Witness to the world. London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott.

Bosch, David J. 1991. Transforming mission. Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Cannon, Dale H. 1994. Different ways of Christian prayer, different ways of being Christian. Mid-stream 33(3): 309-334.

Cochrane, JR, De Gruchy, JW & Petersen R. 1991. In word and deed: Towards a practical theology for social transformation : a framework for reflection and training. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster.

Dalman, Gustav. 1929. Jesus-Jeshua. Studies in the Gospels. New York: KTAV Publishing House.

Foster, Richard J. 1998. Streams of living water. Celebrating the great traditions of Christian faith. New York: HarperCollins.

Gaventa, Beverly R. 1986. From darkness to light. Aspects of conversion in the New Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Haenchen, Ernst. 1971 The Acts of the Apostles. A commentary. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Hauerwas, Stanley. 2004. Performing the faith. Bonhoeffer and the practice of non-violence. London: SPCK.

Hawthorne, G.F. 1983. Philippians. Waco: Word Publishing.

Hengel, Martin. 1979. Acts and the history of earliest Christianity. London: SCM.

Holland, J & Henriot, P. 1983. Social analysis. Linking faith and justice. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Holland, J. 2005. Roots of the pastoral circle in personal experiences and Catholic social tradition, in The pastoral circle revisited: A critical quest for truth and transformation, edited by Frans Wijsen, Peter Henriot and Rodrigo Mejia. Nairobi: Paulines, 23-34.

Karecki, M. 2005. Teaching missiology in context. Adaptations of the pastoral circle, in The pastoral circle revisited: A critical quest for truth and transformation, edited by Frans Wijsen, Peter Henriot and Rodrigo Mejia. Nairobi: Paulines: 159-173.

Kim, Kirsteen. 2005. Reconciling mission: The ministry of healing and reconciliation in the church worldwide. New Delhi: ISPCK.

Kritzinger, JNJ. 1990. Liberating mission in South Africa. Missionalia 18(1): 34-50

Kritzinger, JNJ. 1998. The theological challenge of other religious traditions, in Initiation into Theology. The rich variety of theology and hermeneutics, edited by Simon Maimela and Adrio König. Pretoria: Van Schaik: 231-254.

Kritzinger, JNJ. 2002. A question of mission – A mission of questions. Missionalia 30(1) April: 144-173.

Kritzinger, JNJ. 2007. “The Christian in society”. Reading Barth’s Tambach lecture (1919) in its German context. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 63(4): 1663-1690.

Kritzinger, JNJ and Senokoane, BB. 2007. Tambach remixed: “Christians in South African society”. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 63(4): 1691-1716.

Kritzinger, JNJ. 2008a. Faith to faith. Missiology as encounterology. Verbum et Ecclesia 29(3): 764-790.

Kritzinger, JNJ. 2008b. Liberating whiteness. Engaging the anti-racist dialectic of Steve Biko, in The legacy of Stephen Bantu Biko: Theological challenges, edited by CW du Toit, Pretoria: Unisa, RITR, 89-113.

Langmead, Ross. 2008. Transformed relationships: Reconciliation as the central model for mission. Mission Studies 25(1):5-20.

Lohfink, Gerhard. 1976. The conversion of St Paul. Narrative and history in Acts. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press.

McKnight, Scot. 2007. A community called atonement. Nashville: Abingdon.

Neven, G. 2009. The time that remains. Hans-Georg Geyer in the intellectual debate about a central question in the twentieth century, in Theology as conversation: The significance of dialogue in historical and contemporary theology (Festschrift for Daniel L. Migliore), edited by K.J. Bender and B.L. McCormack.

Overdiep, Wim 1985. Het gevecht om de vijand. Bijbels omgaan met een onwelkome onbekende. Baarn: Ten Have.

Race, Allan. Christians and religious pluralism. Patterns of Christian theology of religions. London: SCM.

Schreiter, Robert J. 1992. Reconciliation. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Schreiter, Robert J. 1998. The ministry of reconciliation. Spirituality and strategies. Maryknoll: Orbis.

Schreiter, Robert J. 2005. Reconciliation as a new paradigm of mission. Paper read at Conference on World Mission and Evangelism in Athens, Greece, 9-16 May 2005.

Volf, M 1996. Exclusion and embrace: A theological exploration of identity, otherness, and reconciliation. Nashville: Abingdon.

Walsh, B J & Keesmaat, S C 2004. Colossians remixed: Subverting the empire. Downer’s Grove: IVP Academic.

Witherington, Ben III. 1994. Paul’s narrative thought world. The tapestry of tragedy and triumph. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox.

[1] Kirsteen Kim has criticised Bosch for this in a recent publication.

[2] One only needs to mention Bosch’s role in PACLA (1976), SACLA (1979), the National Initiative for Reconciliation (NIR), and in numerous intercultural (or interracial) discussion groups in which he was involved to realise that reconciliation was one of the controlling “passions” of his public life.

[3] Both Hawthorne (1983:100) and Witherington (1994:320) point out that this verse should not be read in an individualist way, since the verbs are in the plural, which means that it addresses the church as faith community.

[4] For a more detailed treatment of these features of praxis, see Kritzinger (2002:149f).

[5] Cardinal Josef Cardijn developed this See-Judge-Act approach in the mid-20th century, but it drew on earlier Catholic lay movements (cf Holland 2005:31f).

[6] For an explanation of what each of the seven dimensions mean in my praxis matrix, see Kritzinger (2008a).

[7] In this respect I give recognition to my former colleague at Unisa, Dr Madge Karecki (2005:162), who convinced me of this. She developed a five-dimensional “cycle of mission praxis”, with spirituality at the centre.

[8] For an explanation and development of this term, see Kritzinger (2007).

[9] There are numerous publications on this. One of the first, which perhaps established this threefold typology in distinction from other typologies, was Alan Race (1983). For a survey of these approaches, see Kritzinger (1998).

[10] I developed this notion of ‘short cuts’ across the pastoral cycle in Kritzinger (2002:150f).

[11] I have reflected on the role of interlocutors in a ‘praxis cycle’ in Kritzinger (2002:156).

[12] This sermon was in Afrikaans, and was published with the title “Fasette van versoening” in Die Kerkbode in May 2007.

[13] Many scholars have reflected on this dimension of “the liberation of the oppressor”, since the humanity of an oppressor is as damaged as those s/he has oppressed. For some reflection on this, see Kritzinger (2008).

[14] If the traditionally accepted source hypothesis regarding the origin of the synoptic Gospels holds water, it means that Luke (like Matthew) had Mark in front of him when he wrote his Gospel, and deliberately left out the saying of Jesus on the cross in which he quoted Ps 22.

[15] Brueggemann (1997:317ff) has reflected on Israel’s “countertestimony” in the form of a complaint and lamentation to Yahweh as covenant God, when things go wrong. He points out, however, that it does not imply rejection of God: “at the same time it is an expression of hopeful insistence that if and when the righteous Yahweh is mobilized, the situation will be promptly righted (:321).

[16] Neven’s article is an exposition of the theology of Hans-Georg Geyer.

[17] Lohfink (1976:73-77), who uses a form critical approach, makes interesting observations about the literary motif of ‘double vision’ found in Acts 9:10-16, according to which Ananias and Saul had simultaneous visions. Lohfink attributes this motif, typical of Hellenistic literature, to Luke’s creativity as author.

[18] In 2 Cor 5:14 Paul identifies the love of Christ as the fundamental motive of Christian action for reconciliation.